Theatre

Interview

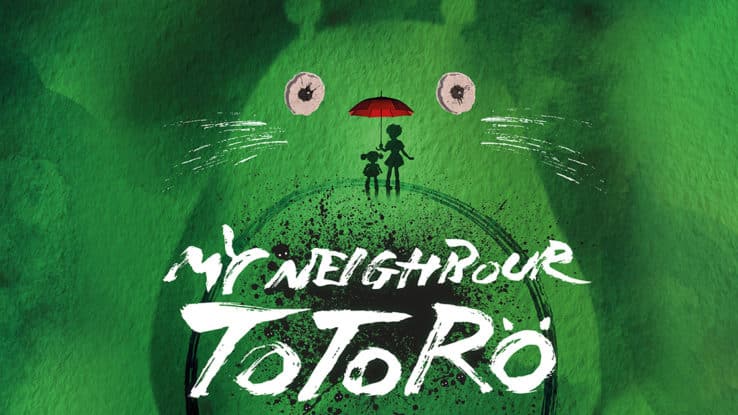

Bringing My Neighbour Totoro to life

Playwright Tom Morton-Smith tells us what it takes to bring Hayao Miyazaki’s classic film to the stage

As stage adaptations go, they don’t get much more challenging than My Neighbour Totoro. Hayao Miyazaki’s 1988 classic is one of the most beloved family films of all time – the story of two young sisters who move into a new home and discover a magical world of forest spirits. Filled with fantastic creatures (some as small as a bug, others as big as a bus), the story is a perfect fit for Studio Ghibli’s distinctive hand-drawn animation. But what about the London stage?

Directed by Phelim McDermott and written by Tom Morton-Smith, the new RSC stage adaptation will feature landmark puppetry to bring Miyazaki’s vision to life, alongside music from the film’s original composer, Joe Hisaishi. The world premiere of My Neighbour Totoro will open at the Barbican for a strictly limited 15-week run from Saturday 8 October 2022, with the show’s creative team now hard at work designing, rehearsing and hand-making the magic behind the scenes.

We caught up with writer Tom Morton-Smith to tell us what we can expect – and to tell us exactly how you bring a catbus to life…

What’s your own history with the film? How has it stayed with you over the years?

In 2001 I saw Spirited Away at the cinema – that was my first introduction to the work of Hayao Miyazaki. I’d never seen anything like it before and I started hunting out Studio Ghibli’s other films either on VHS or DVD. I think I saw Princess Mononoke next, followed by My Neighbour Totoro. I grew up somewhere semi-rural – woodlands and forests were never far away. The two girls playing their games in the fields and trees of the countryside put me in mind of my own childhood.

What was it about this story that spoke to you?

What I love about the film is the space it gives itself. Miyazaki isn’t afraid to let a shot linger on a snail on a leaf, or on some fish in a stream, or the rain falling in a muddy puddle – it invites you to watch such small things again, like you did as a child. It’s not concerned with propelling the plot forward – it invites you to bathe in the animation, in the beautiful character design, in the world Ghibli creates and recreates.

How did you first get involved in this adaptation?

My 2015 play, Oppenheimer, was received quite well – transferring from Stratford-upon-Avon to the West End. Off the back of that success, Pippa Hill (the RSC’s Head of Literary), asked if I had any ideas for a family show. I said almost immediately: My Neighbour Totoro. I always want to write shows that I want to see – ideas that make me think: ‘why hasn’t anyone does this before?’ Luckily for me, Pippa was also a big Ghibli fan and was super excited by the idea. But we had no idea how to get in touch with Studio Ghibli, or who to even approach. Then, some months later, Studio Ghibli independently contacted the RSC. They were thinking of adapting some of their back catalogue for the stage, and because of Matilda, they thought the RSC would be the perfect fit. I think that coincidence/serendipity felt like a good omen all round, and that good feeling has carried us this far.

Did you feel the weight of responsibility when you started work? Not just to Miyazaki, but also to the film’s fans? It’s quite a legacy to inherit…

Absolutely! Our relationship with art – or even the body-of-work of a particular artist – is inherently subjective, but it can also be deeply personal. There are a handful of artists I carry with me as a writer – inspirations, guiding lights – Miyazaki is one of them. To get to work in his world, play in his sandbox, even bring a bit of myself to it – it’s an incredible privilege and honour. But the weight of all of that can be intimidating, so I just have to put that aside whilst I’m writing. I know how important this film is to so many people, and it speaks to people as individuals and to communities in ways that I couldn’t hope to fully understand. So I’ve kept myself open to any and all notes and criticism that has come my way – from producers, dramaturgs, actors, directors, anyone who has had eyes on the script. Adaptation is a delicate thing – even more so when it’s a character and story that is so deeply loved. So I’ve tried to keep my touch light, and tried to remain true to Totoro’s spirit, whilst simultaneously doing what is necessary to transfer an animated movie to the living stage.

Can you talk us through the process of writing – where did you start? Were there any characters that gave you any problems?

I have lost count of the number of times I have seen the film. It’s a constant point of reference. And I’m still finding new things in it. There are scenes in the film that are maybe one or two lines long – or even completely dialogue free – that I’ve had to expand in order for the story to work theatrically. Characters only seen at a distance – Kanta’s father for example – who I’ve named and brought to the foreground. Kanta himself was tricky to write, because he’s not much of a talker! He communicates in the film mostly through grunts and scowls. I love him though – and I hope I’ve done his inarticulacy justice.

How did you approach the story’s fantasy elements? Presumably you had to work closely with the puppetry team to make sure what you were planning was even possible?

The first draft of the script essentially had one impossible thing after impossible thing in the stage directions. Seeing designer Tom Pye and puppet-master Basil Twist navigate those challenges has been a real privilege. There’s been some give and take – and there will be more as we progress. I’m trying to keep the script as fluid as possible in order to accommodate the practical implications of catbuses, soot-gremlins and Totoros.

How important was it to have the involvement of Joe Hisaishi? His score feels so intrinsic to the original film – were you excited to collaborate with him on this?

The soundtrack is such a key part of the original movie, striking just the right balance of magical, mournful and fun. Joe-san himself is an icon. To have not only his blessing, but also his active involvement in what we are doing has been fantastic. During one of our workshops, we put on the CD and pumped it through Barbican’s PA system – it was such a glorious moment. There’s so much warmth in his music.

Without giving away any secrets, what can audiences expect from the production? What do you hope they take away from the stage show?

The best family entertainment – the sort that you carry with you through your whole life – that reveals itself more and more as you age. So, for a toddler, Totoro is a magical adventure with some fantastical friends, for older children and teenagers it’s a coming-of-age story, for adults it’s a tale of how fragile childhood (and life) can be. Essentially, I want to send the kids home with their imaginations overflowing, and their parents’ home with their hearts broken.

After spending so long with the story, and after getting so close to these characters, has the process changed your relationship to the film?

Inevitably I can no longer watch the film as a pure viewer – I’ll always be wearing my adapter’s hat. But there are still moments that transport me, still moments where I’m just delighting in the visuals or the characters or the music. I think what surprised me most was how quickly ‘Totoro’ – as a character and as an idea – made his presence felt. During those lockdown zoom script workshops, and during the times we’ve been able to gather in order to get prototype puppets moving, there were moments where I think all of us present believed that Totoro was real.

My Neighbour Totoro will open at the Barbican from 8 October 2022. Find tickets here.