Theatre

Interview

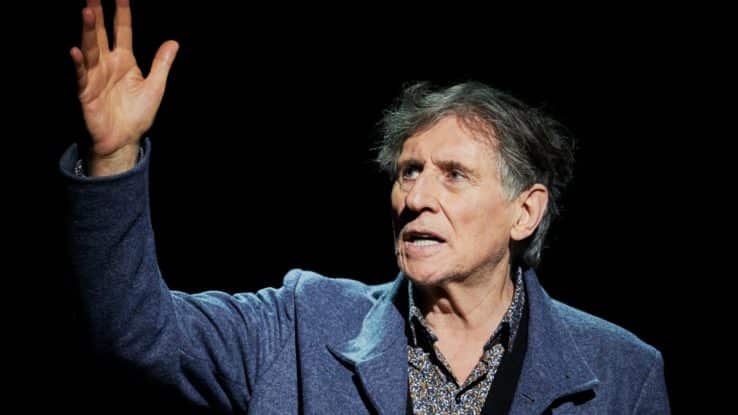

Gabriel Byrne: “I really admire people who speak out through the silence and the shame”

We caught up with the actor to discuss the joys and challenges of bringing his memoir, Walking With Ghosts, to the stage

Gabriel Byrne is astonished to hear that despite my Irish heritage, I have never actually been to Ireland.

“Oh, my God, you have to come over,” the star of Little Women, Miller’s Crossing, In Treatment and Hereditary says. “It’s like going to Toronto and saying, ‘Well, I’ll skip the US.’ I think you’d love it here. Because if you have Irish blood, there’s a part of you that goes back there and says, ‘I kind of know this place, in a weird way’.”

Byrne’s memoir, Walking With Ghosts, is an international affair, whisking him from Dublin to London, to New York, to Los Angeles, to a Venice hotel where he sips champagne with Richard Burton. But countering the whirlwind of success, travel and celebrity is a grounding portrayal of the Ireland that raised him. Byrne’s love for his home country is in places complex, but always undeniable.

Walking With Ghosts – now a one-man play in which Byrne plays all roles – provides a sense of place against a sparse backdrop, and walks the audience through his memories in his own words. The show is set to launch in the West End in September, and is also gearing up for a Broadway run (“It’s just astonishing,” he says, of taking his story to the Great White Way. “I still can’t believe it.”) But, of course, it started in Dublin.

That first show in Dublin. What was that like?

Well, being from Dublin… I think people will tell you that one of the most difficult things, if you’re a footballer or a performer of any kind is playing in front of the home crowd. You have a kind of connection with the audience because you’re from there, but they also tend to look at it with a little less objectivity, which can be good and which can be bad. I have to say, I was really nervous about going back. And I was absolutely astonished and really moved by the reaction of people. The first night, I just walked off the stage, and the stage manager said “You have to go back on! Go back on!” It felt to me like a homecoming.

Obviously this piece is so intensely personal – it couldn’t really get more personal. Does it feel like you’re very much just being yourself onstage, or does it feel like you’re assuming a role that is a version of yourself?

That’s a good question. And honestly I don’t know the answer. The thing is that you couldn’t just get up there and you know, tell your story. You have to use the technique of drama to tell that story. And so on the one hand, I’m aware of the technique of putting the story over. But on the other hand, I’m also aware of the content of it. I was really nervous about putting that content out there. But there is no way around it. You have to be honest, and truthful. And I think if you’re being honest and truthful, the technique takes care of itself, because people don’t respond to technique per se, what they respond to, is the truth or the falsity of what’s being presented to them. And people did respond extremely well to what were, for me, difficult things to talk about.

But my feeling about those kinds of revelations… a playwright can do it with two or three or five people. You’re doing it by yourself, about yourself. And you kind of think, “Oh, my God, will people get this?” But the real reason for doing it, quite honestly, is I don’t see it as a show – I see it more as a play, and the other actor is the audience. Because what I really want to do is to make the audience leave and think about their own lives. The great damage that can happen is when people don’t speak out about the things that truly are meaningful – then it goes into silence. And then once there’s silence, the problem never gets dealt with. That’s why I really admire people who come out and speak out, talk out through the silence and the shame. And so that’s what I’ve done. And it’s shot through with with some humor. Life is not all black.

Was that a motivation for writing Walking With Ghosts in the first place, to combat that silence?

I just believe that every every person has their own story, and all our stories are extraordinary to us and the people around us. And I wrote the book because the world has changed so much since I was a teenager – in the last years, it’s changed so much – that I wanted to put down some kind of a record about what it was like to go through that time, using the senses, the recollection of sight, sound, smell, and so forth. That’s what it started off as, a recollection. And then I structured it in an in a way that that I felt was appropriate to the telling of the story.

That structure is different in the stage production than in the book. What was the reason for that change?

Well, on the page, you can mimic memory, you can be in the present, and then you can go to the past and back to the present. But on the stage, you can’t really do that. when you can, but it’s much more difficult. I think it’s more effective to tell the audience the story in a linear way. Because by telling them in a linear way, you’re building the narrative forward and within that, you can bounce back and forward.

It’s quite a simple set that you’re working with as well.

It is very simple. It’s a mirror that’s broken, it’s fractured. And a mirror is a very powerful symbol. Sometimes I think the audience can see themselves reflected in that mirror. There’s a desk. And we have some sound effects. But the idea is to create a reality that’s it’s not distracting. It goes back to the ancient idea of a storyteller. A guy sitting by a fire, you know, telling a story about the ancient gods or something. He didn’t need a lot of props. But what he did need was the ability to hold the audience’s attention.

We did talk at one stage about newsreel footage and photographs and all that. But we live in a society now that’s so technologically focused, that the imagination sometimes gets short shrift. We’re now tending to record real moments on cameras that should be experienced for the beauty of what they are. But the idea that the audience is there, and they’re with you, on this journey, using their imagination, and then taking something out of the theatre that they can talk about…

A woman came up to me in Dublin, and she said, “There’s a line in that play that affected me. And I began to think about it afterwards.” I was talking about my father. And I said, “I never really listened to you at all. And it’s only now that you’re gone, I hear you.” And she said, “That really affected me because I kind of took my parents for granted, that they’re there, they’re doing their thing, and I’m doing my thing.” And then she said, “I realised they’re not going to be there forever. And I’m going to start actually hearing what they are saying. As the individuals that they are with all their faults, and their virtues, and, and so forth.” And she said, “I realised I had been so busy living my own life, that I had, you know, kind of lost contact with the reality of who they are.”

That really touched me because, you know, I found that to be true with my own parents. Not just parents, but older people or grandmothers or grandfathers. I needed to listen them, to acknowledge them as individuals, I suppose.

It feels as if you’re starting a conversation with the audience that they get to go away and continue.

Yes, exactly. Because when you get the audience thinking about their own lives, that’s the greatest compliment you can get, that they leave the theater thinking about something that they’ve seen. Because that’s when I know if an audience is engaged. Yes, they’re following the story that’s being presented. But they’re also saying, “That’s me. That’s not me. I shouldn’t do that. Maybe I need to do that.” And that, to me, is the greatest part. It’s to give this thing to the audience and say, you know, “This is my way of expressing who I am.” Just that simple interaction between the storyteller and the audience.

It does require you to relive some more difficult, emotional parts of your life on the stage night after night. Is that a draining process at all or have you been able to compartmentalise?

I think you have to come to terms with that and make peace with that. Because you can’t go on the stage every night and suffer the same thing over and over again. I think I’ve come to terms with any of the stuff that I talk about in life, myself, and so it’s not traumatic for me to relive it. To me, it’s just about saying, I will tell you this, and you can make of it what you will. I’m not judging it. I’m not saying it’s right or wrong, I’m just presenting you this information. Because this might be pertinent or relevant to your life.

What was different in the way you prepared for this role compared to the theatre work you’ve done in the past?

Well, the obvious difference is that usually you’re with other actors. If you get stuck, you can look at the other actor and say, “No, it’s not me, it’s you. Oh God, it actually is me.” So you have that net underneath you. For me that the process of rehearsing was filled with a kind of insecurity, of saying, “I hope people can get this.” And there’s something kind of liberating and terrifying about being up there by yourself. It’s given me a whole new respect for stand up comedians, not that I didn’t respect them before, but I now know what they go through before they walk on the stage. Because that material can die. And even if it worked last night, there’s no guarantee it’s gonna work tonight.

But I think you have to push through the fear and the doubt and say, “I’m going to do it. And I’ll live with the consequences.” You have to do that. But that’s true of an awful lot of things in life anyway that if you become overwhelmed by fear or insecurity and you decide not to do something, because you’re afraid of it, that is a decision, of course, but it may not be the right decision. And when you push through the thing that’s difficult to come out the far side, there’s a sense of achievement.

Walking With Ghosts comes to London’s Apollo Theatre from 6 – 17 September. Find tickets here.