Interview

Interview

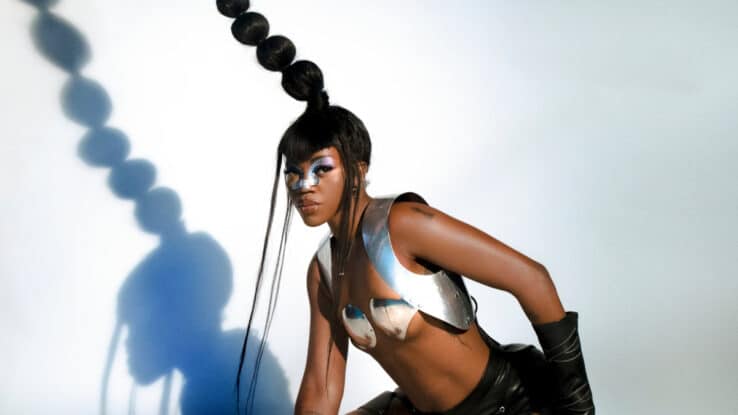

Tkay Maidza: “things come to me on purpose now”

The Australian singer-songwriter and rapper talks her sophomore album, fighting imposter syndrome, and why hip hop represents freedom

Tkay Maidza has had a busy year.

“The album was finished in May,” she recaps. “I’ve had a lot of tours. As we were finishing the project, I had a lot of festivals, and then I toured with Lizzo. And in December last year, which was within six months, that’s when I was with Dua Lipa as well. So, anytime I had free time in between, I finished the album.”

We have a laugh about how casually she’s dropping these names. She confesses that with all the press she’s done surrounding both tours, it doesn’t feel so crazy to say them out loud anymore.

“But they were unbelievable,” she says. “It was amazing. The catering is so good, the food that they have on tour. It’s like the best food you can eat, every day. It was really cool. It felt like I was going into an office every day, and then it was like, the ultimate day. It was almost like my birthday. Even though it was Lizzo’s birthday, really, not my birthday. But I think you get what I mean… It’s just that ultimate celebration. And to be in front of so many people and have the opportunity to have them hear my music is insane.”

Maidza, one of Australia’s major music exports and a leader of the exploding Australian hip hop scene, will soon embark on a huge headline tour of her own. She’ll be stopping by London’s Scala this November, less than two weeks after the release of her sophomore album, Sweet Justice. The record represents a new direction for Maidza, a culmination of all the work she’s done musically and creatively since her debut record, Tkay, in 2016. We caught up with Maidza ahead of the new release to talk about how her approach has changed, and what excites her about Australian rap.

How was it that you got started in music? Both of your parents are scientists, right?

Yeah, they work in mining. We moved from Zimbabwe, and I just remember being a part of a lot of family events where they played music. My parents and my uncles all played guitar or were a part of a band somehow. My weekends would be like that. So I feel like from a young age, I was around music a lot. Probably more than other kids were, more than normal. And when I moved to Australia, I was playing tennis for 10 years, but when I turned 15, I just had this realisation that I didn’t really like the sport that much anymore. My dad had this whole recording studio at our house where he would work on music with his friends. So there was one day where I was like, “Oh my god, I kind of want to see how this works and I want to make a song.” I was just playing around making really silly songs. It was like basically giving a kid a microphone and having them just write songs about, I don’t know, the toilet. That’s literally what I was doing.

My mum – she was always helping me with whatever I did – found this studio that was about two hours away from our place and I would catch two trains there every Monday just to watch other kids write and record. And there was one day where the person who was coordinating the class said, “you’ve never recorded anything, and you’ve been here for at least six months. You should record something today!”

He was surprised by the song I recorded, and he had a DJ friend who ended up turning it into a dubstep rap song. I didn’t listen to that stuff, but it sounded cool. I’d never heard anything like it. And a year later, the guy uploaded it onto the internet and the radio station here called Triple J, and they just started playing it on rotation. I had no idea what was happening. But it’s pretty much a big deal. It’s almost like the BBC playing your song everyday kind of thing. And from that, I met my manager. And the goal for five years was to have a big feature, to work with Calvin Harris or Diplo or something. That was what I was chasing, and I was writing with other producers to hopefully be on their songs. That’s how I grew my profile.

Within the last five years, I had this epiphany. It was… okay, cool, I’m pretty good at making music. But I’m not sure if I’m entirely happy with everything that I’m making. So let’s be more intentional with the songs and make it a whole world so that people understand me more.

I was more involved with making my music videos, press photos and all that stuff. I think that’s where the big change came, when I was being more intentional with what I was talking about, and who I wanted to, hopefully, play shows in front of. I was making stuff that I genuinely really liked.

What in particular inspired that shift?

I had no idea where to go next after my first album. With dance music, you’re chasing whatever the next production is, whatever the next formula is. But where do you go next? I didn’t really have a support system. It turned into me building a little community of friends that I like, regardless of whether we’re working or not. I kind of made it more into a lifestyle. I think most of the best artists have a circle. Everyone likes the same music, everyone’s on the same page. So I was just kind of implementing that.

When you reflect back on those first five years, before that change, what are your thoughts?

It’s interesting, because I feel like both halves of my career are very similar in a lot of ways, but the difference is that now I have more control. I know what the worst could be and what the best could be now, whereas before, I didn’t have control over that, and I didn’t know what was going to happen. It was still really cool that I could work with Martin Solveig and that I could play Reading & Leeds, but it felt very random to me. I had a lot of impostor syndrome because I just didn’t know how everything was happening. This cycle is different. I worked really hard on these songs and they’re exactly the way I want them to sound. So now it’s cool that I get to play these shows. Things come to me on purpose now.

If you could go back to the beginning of your career and talk to your younger self, would you tell her to do anything differently?

No, I would probably just say, don’t be afraid. And this isn’t the last thing you’re going to do. I remember how I thought I had make the best album, but I didn’t understand how I could do it with the situation I was in. It brought a lot of really cool opportunities but I had really bad anxiety at the time. But I feel like that’s what I was meant to go through.

And what can people expect from the new record?

If anything, it’s a progression of the last four years. It’s almost like a “coming into my own self” type of album. I feel like every song I did on there. I was really confident with it. And when I finished the album, I was like, this is the best I can do. I’m really excited for everyone to hear each and every single song because it’s what I would expect to hear from myself.

It feels like over the last decade, as you’ve been finding your identity as an artist, Australian hip hop has also kind of be finding an identity internationally.

There are very talented rappers in Australia – such as Sampa the Great and Genesis Owusu – and it’s exciting to see where we exist in Australia and overseas as well. That’s the cool thing about being Australian though. It’s like, no one really belongs anywhere generally. I think Australians have that advantage to some extent because everyone’s just like, “Where are you from?!”

Who are the Australian artists that you’re really excited about?

I definitely would say Genesis, and Elsy Wameyo is really cool, too. Jerome Farah as well. Those are probably the ones whose names I see quite often and I think they’re [all] dope.

On TikTok you took part in the recent celebration of 50 years of hip hop. You said that to you, hip hop represents freedom. I wonder if you could elaborate a little bit more on that?

It represents freedom because I feel like there are so many ways to say so many different things. When I discovered rap music, I felt like the artists I was listening to were expressing feelings that I couldn’t put words to, and it helped me to embrace my true self more. I was like, “Oh, maybe it’s fine that I have these thoughts because Nicki Minaj said it.” I just remember when I was in high school, anytime I was listening to rap music, I had the most fun. I felt like I was in a room of 20 people when it was actually just me by myself. It’s just that freedom to express and a freedom to be. That’s what hip hop means to me.

What kind of expression are you talking about, specifically?

The ability to choose whatever you want. It’s like, if you’re an alt rap kid, there’s Kendrick Lamar who genre-bends, and makes it sound classical and timeless. There’s also the idea that you can just wear all black and listen to drill, and that’s cool, too. Or you could do pop rap – there are no boundaries to it. Whereas in other genres, I think there’s more tape around how far you can go. I just feel like rap music always brings a new generation of people because there are no boundaries.

Do you feel that’s why rap and hip hop often feel so tied to the cultural conversation?

Yeah, I feel like rap music is always going against whatever the social problem is. And there’s also that sense that you’re not alone. And it’s okay if you kind of disagree with the government, if you disagree with the way girls or guys are acting right now. It’s like a debate that’s always opposite of whatever’s popular, but then that becomes a popular thing. And then there’ll be a new thing that goes against that.

With social activism, I feel like whatever it is, there’s gonna be a song about it that everyone likes. It’s really cool that hip hop brings people together like that.

Tkay Maidza’s second album, Sweet Justice, will be available to stream 3 November.

Tkay Maidza will play London’s Scala on 14 November – find tickets here.