Interview

Interview

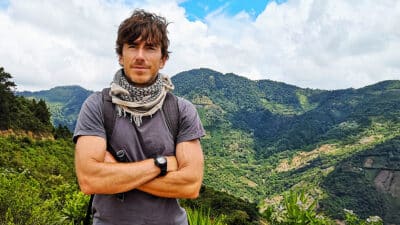

Kabaka Pyramid: “Reggae artists need to be more strategic”

The Grammy-winning artist shows us what the future of dancehall and reggae looks like

Kabaka Pyramid’s The Kalling just won Best Reggae Album at the Grammys. It’s a lot to take in for any artist, but for Kabaka, a first-time nominee who has been fighting for years to gain mainstream recognition, it’s a particularly meaningful victory.

“It’s been a process to soak it in,” he says. “People are taking what we’re doing a lot more seriously. This is why we do it, you know, so that we can keep growing and keep reaching new milestones.”

He’s now dealing with a new level of notoriety, the kind where your tweets become headlines and people are zeroed in on your every move. But Kabaka is approaching it all with a level head and the understanding that his individual success opens the door for reggae artists coming up behind him. Now he prepares for a string of shows in the UK this April, he gets a chance to see what kind of impact The Kalling has made overseas.

“We’re looking forward to the shows in the UK, post-Grammy, to see what the vibe is,” he says. “We know people are listening to the album over there, and it’s sometimes getting playlisted on BBC and different things. I do think England is super important for Jamaican artists because we’re so embedded into the culture there.”

We spoke to Kabaka ahead of his UK shows about the process of creating his Grammy-winning album and what the future of reggae looks like to him.

What’s it been like entering that space where now you’re amongst Grammy winners and all these other artists from different genres who get a lot of respect in the music industry?

It’s a good feeling. You know, I feel much more respected for what I do. I’ve always kind of been an artist that a lot of people respect, but who is still maybe a bit under-appreciated. Winning the Grammy kind of helped to get rid of that stigma. It’s tangible. You know what I mean? Different people have been reaching out, people that didn’t reach out before, and on social media the support is a lot stronger. So in all facets of what we’re doing, you see improvement.

Was it something that you thought about when you were making the album, that this might be an award-winning piece of work?

You know, the thought comes across my mind every now and then when making music, but it’s not something I really banked on or told myself I was guaranteed or anything like that. But I remember when Gramps Morgan came to the studio, he was like, “This is a Grammy album. This is definitely a Grammy album. And, you know, things like that helped to build my confidence, my anticipation. But even after the nomination, I was the only first-time nominee in this Grammy class. And so I was like, the chances are still kind of slim. But then still being optimistic and positive about it.

Did you feel while you were making the album that this was something special, or stronger compared to previous records?

Yeah, definitely. I knew we were up to something special from very early on in the process. Because, you know, the previous album I did had a lot of different producers on it, and a lot of different sonic textures. But this album, with everything being done by Damian Marley in his studio in Miami, there was a cohesiveness that we knew people would appreciate. I feel like the songwriting stepped up, the production stepped up… This is the best piece of work I’ve put together since I’ve been doing this music. I definitely felt like it was something to be proud of from the get go.

How far through the process did you start to notice that?

It was earlier last year, because at that point we had the majority of the songs done, and then we started messing around with ideas of sampling some other records. So that’s when ‘Fade Away’ became ‘Faded Away’ [sampling Junior Byles]. ‘Mystic Man’ with a ‘c’ [Peter Tosh] became ‘Mystik Man’ with a ‘k’. We started doing versions of these great records and that was when we knew we had everything we needed. We had the substance tracks, we had solid reggae. So then the stuff with the samples just really brought it over the top and brought everything together, you know? And then especially with Buju Banton’s verse on ‘Faded Away’…

Yeah, you you had a lot of great collaborations on this album.

‘Faded Away’ with Buju, ‘The Kalling’ with Stephen Marley, Jesse Royal, and Protoje… ‘Red, Gold and Green’ [with Damian Marley] by the numbers has been the most successful song on the album so far. And, you know, all of these we knew had high potential to be successful records. ‘Grateful’ is very unique and special with the production and the lyrics and just the hopefulness of the chorus and everything. Jemere Morgan did great.

As you said, there’s collabs all over. You know, this is actually Nathalia’s first record as a recording artist. So that was special, working with her [on ‘Stand Up’]… It’s a team album, really. Even Joe Mercer, who passed in December, helped write ‘Mary Jane’, so rest in peace Joe. I’m glad that we were able to collaborate on this album, even though he wasn’t featured.

Do you think you’ll want to keep working with the same close-knit team that you worked with on this album?

Yeah, but I want to incorporate maybe one or two more producers. It depends on the project. When I play my beats for Damian, he’s like, “Yeah, I definitely see where you could do a lot of production on the next album, because, you know, it’s stepping up now.” The synergy is there, and I feel like we definitely don’t want to lose that – we want to maximize that. I could see different scenarios playing out down the line.

Is the production side of things that something that you’ve always been very involved in?

I’ve always been interested in it, learning and experimenting, but my general ability has grown over the years. I remember messing around with Fruity Loops 3 and Fruity Loops 4 20 years ago, making beats and things like that. And yeah, when I look to where I’m at now in terms of my production, it’s improved a lot and I’m really happy with the growth. I definitely want to do more.

Take me back to where your journey in music started. When did you start getting interested in it as a potential career?

I would say right after high school. Towards the end of high school, we had a sound system. Me and my brother put together a little studio at home. And then eventually he started making beats and then me and all my school friends started writing music and experimenting with lyrics – reggae, dancehall, hip-hop, and I couldn’t sing to save my life. It was easier for me to rap. Like, I used to listen to a lotta hip hop. So I used to recite all the lines from Canibus, Big Pun, Biggie Smalls, Nas, Wu Tang. Thanks to all of these rappers I used to be pretty proficient at rapping. So that’s kind of how I felt comfortable expressing myself early on. And then over the next 10 years from like, 2002-2011, I developed my voice.

That’s still something that’s developing too. Even with this album, my ability to sing has improved a lot compared to my first regular project back in 2011. You could still hear the heavy hip-hop influence in my first project, Rebel Music. It was free, and we called it an EP, because we didn’t want people to think of it as an album. But it was really like 10 tracks. And by the next year I was on tour in Europe, performing those songs. That’s when the career started.

Why was it that you wanted to move towards reggae rather than hip-hop?

I always saw myself doing both, because of my genuine love for them. I always wanted to bridge that gap. And I always appreciated when hip-hop artists collaborated with reggae and dancehall artists. But it was really reggae that changed my life, that brought me to Rastafari and put me on a kind of spiritual journey. I always knew that reggae music was the more powerful genre for me, in my mind, in terms of wanting to have an impact on the world. I think reggae music is a channel for that. I think hip-hop is more of a creative outlet, like a creative expression of the self. Reggae is about affecting the masses with powerful messages in music.

Both are avenues I’ve always wanted to explore, but I knew that hip-hop wouldn’t really work coming from Jamaica. People don’t understand why a Jamaican would be rapping, you know? People don’t get it. I would be rapping on stage and people just kind of looked at me, confused. But I always knew that my destiny would be to work on the reggae side and improve my voice. Because with reggae, I have to have melody, I have to know how to stay on the key, on the rhythm, on the beat. I just didn’t know any of that early on. I had no clue.

Was that a steep learning curve, learning how to sing rather than rap?

Yeah, definitely. For me, I mean. A lot of reggae artists grow up in the church, and they’re in the choir from when they’re young, and they kind of develop that ability. Or maybe their parents are singers and they grew up going to the studio. I didn’t have any of that. So for me, it was a steep learning curve, as you say.

You’ve been praised from very early in your career for doing something hip-hop does with your lyrics: writing very socially conscious, very issue-driven music. Was that something you wanted to do from the start of your career?

Right from the start, that was the mission. Sizzla Kalonji, he was the one whose music had the biggest impact on me – changing my life, changing my diet, my spiritual worldview and everything, you know, my Afrocentricity – he was the one who really spearheaded that. So I always knew the power that the music can have and the ability to change lives and that was always the mission. But from my creative perspective, it was always about the lyrics because I’m more a cerebral type of person than naturally musical. Formulating lyrics is a more mental process for me, you know. So that’s where my strength is in music. Obviously I’ve grown musically as well, and I can play a little guitar now and do my thing and play a little bit of keys when I’m making beats and stuff. But it’s largely a cerebral thing.

Your first official debut studio album was released nearly a decade ago – how do you reflect back on that record compared to where you are now?

That record was interesting, because after I released Rebel Music for free, we started getting a lot of tracks sent to me from a lot of producers. I just spent that time trying to lay the groundwork and trying to piggyback off of the platforms that these producers had.

Back in those days, nobody did any business deals with producers. You just record the song, and they release it, they take the income from it, and you go out and you perform and that’s how you make your money as an artist. We kind of tricked the system, and we were like, “We’ll license our version of this, and then we’ll keep our income from that. You keep your income from your version.” That was a whole thing. It was more like a business move. That’s kind of how I look at it now. And that’s cool. I think it worked as well. And to this day, you know, every three months, you still earn an income from that.

And then was there a point later on in your career where you started to feel like this was artistically how you wanted to be working, and you were hitting your stride in that sense?

It’s hard to say at what point but I think songs like ‘Well Done’ kind of changed my trajectory. That was the first song I did with Damian Marley. And that became the song that people identified me with.

I had local hits in Jaimaca before that, but I think ‘Well Done’ kind of cemented my status in the business and it’s something that the average American knew, and that helped internationally. Shortly after that we released the Accurate mixtape. I sang with Ray Cohen – I mean I’m a huge fan of everybody in Wu Tang Clan. While working on the mixtape, we started working on the Kontraband album. And then when Kontraband came out, that kind of really cemented my status, like, Kabaka is here to stay.

And now obviously, it’s a different level. What are you looking forward over the next few years?

So much more. More music. More Grammys? You know, as an artist, there are certain things that kind of measure where you’re at, like, the type of festivals you do, where your name is on the lineup, and all of these kinds of things. So, you know, over the next two to three years, I want to be headlining some of the big reggae festivals. A lot of them, my name is on the second level or the third level. We look at those little milestones to say, “Alright, four years ago, I was way down here…”.

I am headlining a couple of smaller festivals this year in the US too. I just want to keep rising. I don’t want to be one of those artists that stay on one level. As long as I’m young and healthy, and keep rising to new levels. I wasn’t to start to bring other artists on tour too, because that’s what I see the bands in the US are doing. They’re doing their own tours, and they’re bringing second tier, third tier, fourth tier artists with them on the road, and they kind of have a whole ecosystem.

What do you feel like the future of reggae looks like?

I’ll tell you what I think is a good strategy for reggae music. You have two sides, you have reggae and dancehall. I think for reggae, the real strength is with the touring. I think we should be looking to be able to do our own tours with 15-20,000 people coming out to shows. I see that as kind of difficult in Europe because mostly it’s about festivals and then you do some club dates and stuff like that. But in the US, I’ve seen the way these bands do it, and I love what the Marley brothers are doing – they’re penetrating that market over there so that in the years to come we’ll have a platform to be able to do that as Jamaican artists.

I think with the dancehall side of things, I want to see more focus on the UK and pushing the music from there because I think dancehall is with world music right now, just in terms of the beats and the tempos. And what you see happening with Afrobeat is it’s kind of channeled through the UK before going on to the rest of the world. That’s kind of what I see dancerhall doing.

But the lyrics have to be a bit more palatable for the world to absorb. I think dancehall music tends to be super tailored towards Jamaican and Caribbean people, and people who understand the dialects. And there’s even a lot of derogatory lyrics too and I think that needs to be cleaned up a bit so that there can be more international success. Because, you know, the diasporic success is cool. And a lot of artists are doing very well. I think we can affect the world on a much larger scale if we’re just a little bit more strategic.

Kabaka Pyramid is playing UK dates in April 2023. Find tickets here.