Theatre

Interview

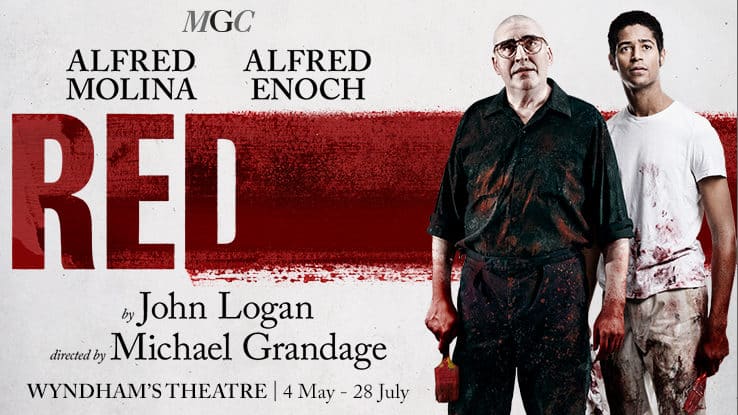

Interview: cast and creative of hit play Red

We chat to director Michael Grandage and stars Alfred Molina and Alfred Enoch ahead of the play’s opening at the Wyndham’s Theatre in May.

John Logan’s play Red first premiered in London nine years ago. Directed by Michael Grandage and starring Alfred Molina and Eddie Redmayne, it then transferred to Broadway for a limited engagement where it won the Tony Award for Best Play. It later opened in Los Angeles, again with Molina in the lead role.

Next month, acclaimed director Grandage brings the production back to the West End for the play’s first major London revival since it premiered. Molina will again reprise his role as expressionist painter Mark Rothko, while the role of his assistant, Ken, will this time be played by rising star Alfred Enoch – most known for his role in the TV series How To Get Away With Murder.

We caught up with Grandage, Molina and Enoch as they got stuck into rehearsals for the new production ahead of it’s opening next month.

Michael, you directed the premiere of Red in 2009, and now return to direct the first ever UK revival – what’s brought you back to the show? And why does now feel like the right time for revive it?

Michael Grandage. The characters in Red argue about the politics and the background to being an artist. I wanted to do this play again now because the central theme is “why art matters”. And I don’t just mean painting, I mean all art – music, plays, literature, the lot – and with the cuts in funding we’re seeing and the huge debates going on about how you continue to make art in society, here we have a great, great painter of the 20th century really talking about his central ethos and why it matters.

Alfred, what can you tell us about the characters you and Alfie play?

Alfred Molina. Well I play Mark Rothko, the painter, and Alfie plays a young man named Ken who arrives for the job of my new assistant. And it’s really about their relationship over a period of about two years in which Rothko has been commissioned to paint these huge murals for what was then the new Four Seasons restaurant in New York, which was on the ground floor of the Seagrams Building.

What happens during that period?

AM. What made that time interesting was that it was the joining up of two really interesting things – one was that Rothko was the absolute king of abstract expressionism and cutting-edge art, and the Seagrams Building was the cutting edge building of that period. The designers of the building were using revolutionary techniques and materials that had never been used before: copper cladding and all kinds of chrome and glass that had never been seen before. And so this partnership was the coming together of two really important movements that the world was obsessed with.

And so it’s Rothko’s journey during that time, but it’s also the journey between these two men, who are very different in age, and there’s a father-son element to their relationship, a master-servant element, and it’s the way that relationship changes through the process of the work that they’re engaged in.

Alfie, do you see any parallels between your characters – that idea of Ken learning from the master of art, and you as an up-and-coming actor learning from the master in Alfred?

Alfred Enoch. Ha! Well thankfully the rehearsal room for this was a much more welcoming room than the one that Ken walks into!

AM. Yes, Alfie is having a nicer time than Ken did, I can tell you that much!

AE. But I do remember at one point reading the script and thinking, “Oh gosh, what I’ve let myself in for?” But not at all, honestly, it’s been such a pleasure.

So aside from Alfie joining the cast, what else feels different about the show this time?

MG. For me I think it’s a more pertinent story right now than it was even when it was first written. People are hungry for that debate [about access to art] now – what is happening, how do we reach people – not just with the theatre, but with all art forms. And at the centre of this play that debate lies; and a debate right now about why it matters seems so important.

AM. I also think it’s important to say that with all the different manifestations of the cast over all the productions – we did it with Eddie Redmayne in London and New York, and I did it in LA with Jonathan Groff – and now with Alfie, Michael and I thought that whoever it was who came to play Ken, that actor was 50% of the cast and therefore deserved 50% of the play.

MG. Yes, so it was never about just recreating what we’d done before, it was always about rediscovering the play. And so we were very conscious of saying “this is yours now, and whatever you do with this is valid.”

AE. And that is not the deal Ken gets. Ken’s relationship is not 50/50.

And Alfie, what do you think you’ve brought to show specifically?

AE. Well I think it’s my responsibility to seize the opportunity that’s presented by that freedom.

AM. Alfie’s too modest to say this himself, but he comes with an amazing amount of skill and intelligence, sensitivity and awareness, and these are things you learn as an actor as you go through your career. If I’d been as aware and intelligent and skilled when I was his age, I would’ve been very, very happy.

AE. Thanks for that – I’ll pay you later!

Alfred, is your approach different when playing someone who actually existed?

AM. It is a little bit. When you’re portraying someone who actually existed – either contemporary or historically – there is a responsibly not to misrepresent that person, epecially when there’s documented material on them; and, of course, there’s loads on Rothko! So I couldn’t come in and decide to do it with a Russian accent, for example, or decide to make him more sympathetic with a limp or something…

AE. Which, obviously I can do with Ken.

AM. Yes, you easily could give Ken a limp if you wanted to…

[Laughter]

In the play, how much is there of Rothko the person versus Rothko the artist?

AM. That’s an interesting one because I think its 50-50. So much of what made Rothko the artist he was is so closely tied-up to what his values were as a human being: he was very strict, very intellectual, very unforgiving when it came to the failings of others, very demanding of himself. He was prone to drinking – but then when he drank the suggestion seems to be that that freed something in him – and he was snob. I think all of those personality traits absolutely impacted on his painting.

AE. There’s this great moment in the play where Ken is just making small talk and he says something about a Chinese restaurant closing down, and Rothko comes up with this whole spiritual reason why its closing is a part of the circle of life, and Ken says, “You’re not one for small talk, are you?” and Rothko just says, “Yeah, ‘cause it’s small.”

AM. Eleanor Roosevelt once said there’s three levels of conversation: people talk about events, then they talk about people, then they talk about ideas. And that’s what Rothko was interested in: ideas.

MG. And the timing couldn’t be better to retell this story about Rothko’s ideas and his ideology because the play is absolutely about what’s going on right now. Like all great drama, it doesn’t need to be set now to have the debate about now, and, in fact, its slightly better that its set in another time because it means you can use that time and see the present through the prism of that era – and that’s just fascinating.

Red opens at the Wyndham’s Theatre on 4 May. Get tickets now through Ticketmaster.co.uk